Obviously the one and only answer is scientism. But since scarcely anybody realizes how steeped they and the culture are in scidolatory, the first battle is convincing them of such. Only then can alternatives be outlined. Too much work for 600 words.

So let’s pick off a low-hanging over-ripe worm-infested fruit: hypothesis tests. Out they go, to join phlogiston, NPR, ketchup on hotdogs, pitchers batting, and other wispy intellectual ideas destructive of sanity and souls.

What are hypothesis tests? Primarily a way to award gold stickers to cherished beliefs. Users are allowed to say, “Not only is what I desire important, it is statistically significant.” The appendage is meant to be a conversation stopper. “Oh, well, if it’s statistically significant, how can I object?”

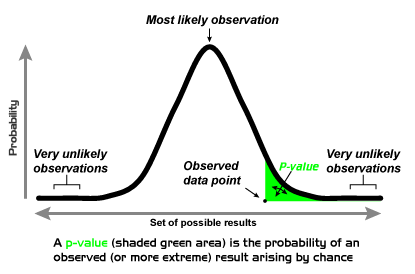

Now there are all kinds of theoretical niceties about these creatures, lists of dos and don’t, stern cautions issued by statisticians without number, distinctions between correlation and causation…but nobody ever remembers them. Not in the breathless chase for wee p-values. And anyway, most of these theoretical considerations have nothing to do with what anybody wants to know. Hypothesis tests don’t answer the questions people ask, and when they do it’s because hypothesis tests have fooled them into asking the wrong questions.

Sociologist wants to know if sex has anything to do with the drinking habits of the “underrepresented” group o’ the hour. Of course it does: all history shows that men and women are different. The real question is how much does knowing a person is male and not female change the uncertainty of a person’s drinking habits? It is not whether, but how much.

Nevertheless, a hypothesis test can say “no effect at all”, which is wrong a priori for most things. Consider that it is as rare as a believers in Harvard’s Department of Theology that anybody actually believes a “null” hypothesis.

Climatologist wants to know whether a temperature which he has been measuring yearly has indicated a trend. Now all he has to do is look. Has the temperature gone up since the start? Then it has gone up. Has it gone down? Then it has gone down. Has it wiggled to and fro? Then it is has…skip it. Because that’s too simple for Science.

So the climatologist unnecessarily complicates the situation—which, incidentally, is the working definition for many sciences—by fitting some arbitrary (usually straight line) model to the temperature and calls on the hypothesis tell him what he has refused to believe of his eyes.

His practice might make sense if the climatologist thought the physics must indicate a linear change in temperature, or that he was going to use his model to predict future temperatures. As it is, he does neither. He only asks if temperature has “significantly” changed—an entirely man-made metaphysical status. Useless.

Useless because of the host of things ignored. Why this start date? Why this end date? Why this data and not other? Would a different model (or different test statistic) indicate non-significance?

It’s the same any time hypothesis tests are used. There are scores of external, qualifying propositions (like start and stop dates) which are scantly recalled when making the test, and immediately purged from memory after the p-value is revealed. That thing, that absurd thing, becomes all that is remembered.

Well, on and on. What to do instead? Simple. Abandon unnecessary, arbitrary quantification. Use (in science) probability models to express uncertainty in observables and not for any other purpose.

Odds of happening? Same as New York Times finding fault with our dear leader.

Update From Steve Brookline below:

Discover more from William M. Briggs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

OTOH, in some situations — what Weaver, von Hayek, and others call “disorganized complexity” — it may be perfectly appropriate. If, for example, I want to know whether two machines are producing product at about the same mean value. Iterative manufacture is supposed to make each part identical. It never does, but the question is how far different can they be before we say that one machine or the other needs adjustment? (This was the second part of Box’s famous dictum.) The real issue is that techniques developed for thermodynamics, quality control, and other instances of disorganized complexity are being applied to instances of organized complexity; that is, systems in which there is not only a large number of elements, but those elements are structured to one another in such a way as to comprise a “whole.” Economies and genomes are examples. Neither buyers and sellers not genes ramble about at random. Weaver contended that the mathematical science of the 19th century was appropriate to “organized simplicity” (a few elements, deterministically ordered), and the statistical science of the early 20th century was appropriate to “disorganized complexity.” But a different approach was needed for systems of “organized complexity.”

We really don’t need hypotheses anyway. We just start with the desired result, throw in some graphs with lines that support what we want to be true. Make up some raw data and then lose or hide it and viola! Scientific consensus! Worked very, very well for climate science. Of course, we still have to thousands to groups for creating the graphs and the press releases, but we always know what answer we’ll get so it’s worth it. 🙂

On the serious side, one would hope that the fiasco of climate change would help put to rest scientism. It certainly is damaging the discipline of science. How long before the godlike worship of science goes and the belief it knows everything goes is hard to estimate. Can’t get a wee p value on it……

YOS,

Nope, banish them even there. For if the “null” might be true you want to know how likely it is true. And HTs can’t give you that.

Hypothesis tests confuse making a decision about the truth of some proposition with the probability the proposition is true. HTs cannot give the probability any hypothesis is true. HTs conflate probabilities and decisions, which is always suboptimal.

Update I bet nobody ever believes that two manufacturing processes can produce identical means (a mean is an observation). What you’re more likely interested in is “the probability process A produces more than B” or variants (“A twice as much as B”, etc. etc.). That can be computed. Only then does the decision analysis kick in. Our cry is: Restore observables to probability!

Sheri,

When I say ban hypothesis tests I do not say ban hypotheses. The opposite is true. I delight in hypotheses. So much I’d like to know the probability of their truth. This is what hypothesis tests are expressly designed not to do.

In my view this is barking under the wrong tree. Blaming the tool for current ills of scientific community. Hypothesis and testing of it are good things. Approximations and starting from simple (linear) models is a good thing. Modern technology built on such step-by-step science proves it.

What is bad is infiltration of ideology into the science. In the (not so long ago) past it was the rigorous system of peer checks and balances, peer skepticism, peer re-examination that have kept poor science and ridiculous conclusions to bubble up. Unfortunately, first through social sciences (where anyway “everything goes” that is PC) and than mainly through AGW nonsense, ideology crept in. Now, instead of true scientific peer checks there is enormous ideological and PC peer checking. That is the real problem. Now, proper tools of hypothesis and checking it can be perverted to push proper ideological results, not proper scientific results.

History of it is also very telling in explaining how this “Overton window” of ideology related to AGW have moved: Famous Al Gore hockey stick temperature prediction graph was simplification of actual “science” published by NOAA. However, even those ideologs of the time haven’t dared not to be scientifically honest – find the original paper and read it: they clearly state in it that human “fudge factors” in data interpretation are,… wait for it,… 400%. They tweaked to ideology but they admitted it. Roll up to 2011. CERN. Cloud experiment. Proof of the main driver of climate/temperature of the Earth (proportion of high energy particles in the total energy received by Earth, matter of higher energy particles being more efficient in heating Earth via interaction with atmospheric water vapor). Not CO2, not AGW, hence… official ban on interpretation of the Cloud Experiment data by CERN. Not even a trace of honesty or science. Ban on par with Vatican vs. Galileo (just worse as that other one was between ideology not claiming any scientific basis vs. science… CERN and AGW crowd wave their “allegiance to the science and only science” as hard as they can).

dusanaml,

Appropriate to blame tool when the tool doesn’t work, and doesn’t do what you thought it did. Most have no idea what the hypothesis test actually did for them.

But I’m with you on ideology.

Briggs–I guess I should have put that /sarc tag on, right? Sorry……

Of course there are temperature trends from year to year — the temperature on January 1 is dependent on the temperature on December 31, and December 31 is dependent on December 30, on and on. Temperature is not a new roll of the dice, so to speak. So the null hypothesis is false in these instances.

Low-hanging fruit indeed, but we still teach it to students! At least I explain very carefully all the additionals to the null hypothesis testing formulation that show that our *belief* in null hypothesis testing is only that: a belief held in the absence of any empirical data.

Amen brother! HTs should be considered a curiosity, a statistical teqnique one learns perhaps the last semester in university, if ever. Instead it dominates Science (at least psychology) and why is a mystery, to me at least…

You may be in agreement with climate scientist Doug McNeall, who wrote the other day

“If somebody asks if something is statistically significant, they probably don’t know what it means.”

http://dougmcneall.wordpress.com/2014/02/03/a-brief-observation-on-statistical-significance/

Rasmus: As someone who majored in chemistry and psychology, my best explanation for why HT is so popular in psychology is that it makes psychology look more like science. Unlike chemistry or physics, psychology reallly has no hard and fast rules or data. However, that absence made it suspect and thrown into “psuedoscience” by the hard sciences. Enter statistical significance. Now, it’s real science. We can prove things–or at least that things are greater than chance. It’s “real” science. Honestly, it’s pretty much the only way to actually asses the effectiveness of the discipline on a large scale–or ineffectiveness. I guess since it worked well there, other scientists decided that “statistically significant’ could be used to persuade people. It seems to have snowballed from there.

I very seldom used hypothesis tests in quality assurance. We preferred Shewhart charts. Our beef against hypotests was that they were “static” rather than dynamic. But on occasion… You see, two machines making the same part are supposed to produce pretty much the same dimensions. They are never identical identical, but they must be practically identical. But you must show proper respect for the beta risk and use the right sample sizes and all. The whole point is to keep your cotton-picking fingers off the machine unless you have evidence “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the machine really is performing differently. At that point, you investigate further to confirm and diagnose.

++++++

Ban on par with Vatican vs. Galileo (just worse as that other one was between ideology not claiming any scientific basis vs. science…

Not true. Galileo did claim a scientific basis. He just had no empirical proofs. http://tofspot.blogspot.com/2013/08/the-great-ptolemaic-smackdown.html

WHAT?

I can even begin to describe how much I disagree with you. I could never eat a hot dog without ketchup.

There have been times when I thought I understood this business about a null hypothesis – but never after I sobered up.

I see on the Edge.org site that a chap by the name of Gerd Gigerenzer is arguing against statistical rituals too.

There is also a proposal by some bloke at NASA GISS called Gavin Schmidt arguing against “Simple Answers”. I suppose that that means that “The Science” isn’t “Settled” or “Overwhelming” after all.

Gareth,

Gigerenzer is a good guy; I recommend his books and papers. And I too was shocked to see Gavin’s perfectly reasonable answer. I did a triple take and then headed for the bottle to ensure it wasn’t all in my perfervid imagination.

Gareth/Briggs: Thanks for drawing my attention to these two authors on Edge. The common thread in climate science is “we have the math and statistics to ‘prove’ this”. Nothing seems to get said believers to understand we do not have said ‘proof’ (though Mann did just through out the ‘proof’ and head straight for probability and CI) for what is being presented. I am surprised by Gavin’s response too.

I don’t care what people say, I like Gavin.

Ketchup on a hot dog?

Dirty Harry said it best…

Video link

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xz84GKxy7b0

This reminds me of http://xkcd.com/1132/

I was with you until you badmouthed pitchers batting.

Used properly, hypothesis testing plays an indispensible role in the scientific method of investigation. When a model has been built and statistically validated, there is the risk that it seems to provide information about the outcomes of events when it provides no such information. The p-value that is extracted from the validation data quantifies this risk.

Well I agree with your criticism of scientism and the fundamental mistakes people make while justifying their ideological positions I still see a need for the ‘null hypothesis’.

Consider the following situation.

Medical researchers have developed a molecule that they think may cure disease D. There are no known treatments for D and the costs of bringing the treatment to market, given various regulatory hurdles, is more than $500M.

Is the molecule, call it ‘x’, effective?

I assume the only way to proceed is to develop a trial involving ‘x’ and humans with the disease. Knowing so little I don’t see how one can avoid saying what we want to know is if ‘x’ is more effective than a placebo. Or rephrased as a null hypothesis – ‘x’ is no better than a placebo.

We design the study as a ‘double blind, double dumb’ test of ‘x’ and look at the results.

Assume for a second that the disease ‘D’ was cured for 85% of the subjects taking ‘x’ compared to 18% of those taking the placebo.

Without thinking about ‘wee p values’ I think most people looking at the test results would say that we now have some solid evidence that molecule ‘x’ seems to be more effective than a placebo. Or to say the same thing in another way we reject the idea that ‘x’ has no effect. Given the results the researchers can argue that more work should be done with ‘x’ on the long road that might bring ‘x’ to the market.

The study results should be tested again in other trials to answer the question, “If we replicate the study do we get similar results?â€

So, in this ‘thought’ experiment we used a ‘null hypothesis’ and avoided ‘wee p values’. That said I think that the problem with some researchers is adding all sorts of unnecessary artifacts (e.g., ‘wee p values’) to an extremely useful question. In this case does ‘x’ make a difference.

Wit’s End,

Great example, but, nope, no hypothesis test needed. What you want is, given the data you’ve observed, the probability the drug cures the disease and the probability the placebo cures the disease. One will be higher than the other. Simple, right? Simple to understand, I mean. Bit harder to compute.

Also take a gander at this series.

I agree with Ye Olde Statisician. In my experience with QA, probability distributions are mostly used in marketing for their dog and pony shows. In production we use control charts that track a specified number of samples to give a reasonable picture of performance based upon the target spec and upper and lower control limits. Probability distributions are something that we make for the boss to mull over and stay out of our hair 🙂